By David Kier

www.vivabaja.com

Co-author of ‘The Old Missions of Baja & Alta California, 1697-1834’

By the end of 1791, the first five Dominican California missions were established along El Camino Real, securing the corridor between the peninsula and San Diego. The interior could now be brought under control with ‘mountain missions.’ The Indian attacks would be halted by “Christianizing the heathens,” or so the Spanish government believed.

The northern Baja California mountain valleys and meadows were first explored by José Velazquez, in November of 1775. Velazquez was ordered by Governor Neve to explore the northern gulf coast for a closer port than the Bay of San Luis Gonzaga, to serve the new Dominican missions. In May of 1793, Lieutenant-governor Arrillaga sent out an expedition inland to find potential mountain mission sites. Two of the mission sites were found to be the most suitable. One was northeast of San Vicente near a pass leading to the Colorado River. The other was east of Mission Santo Domingo in a high mountain meadow. In a letter dated January 15, 1794, Arrillaga stated that Mission San Pedro Mártir would be founded east of Santo Domingo that April.

Mission San Pedro Mártir de Verona was established on April 27, 1794 by Padre Caietano Pallás with Padre Juan Pablo Grijálva and Padre José Loriente. The first site for the mission was a place known to the native Kiliwa Indians as ‘Casilepe’ and is a meadow, today called La Grulla. It was at an elevation of 6,785 feet. The exact location was unknown until an expedition in 1991 revealed cut stone foundation blocks in a pattern and scale that was of European origin. Some 60 Kilawa Indians joined the mission in its beginning.

Less than three months passed before a location change was requested. On July 18, 1794, Padre Pallás wrote the following to Governor Borica: “The new foundation has not continued with the happiness with which it began. The crops have frozen and I have determined to move it to work at another place, situated on the western slope of the Sierra about three leagues distant from the other.” On July 19, 1794, Padre Pallás wrote: “… the missionary at San Pedro Mártir says he will move the week that now ends, because of frosts and annoyances.” On July 29, Pallás requested permission to execute the transfer from Casilepe to the location known to the Kilawa natives as ‘Ajantequedo’. Governor Borica responded on August 10 to permit the transfer to a more fertile and sheltered site. The second mission site is seven miles south and over 1,700 feet lower in elevation than the first.

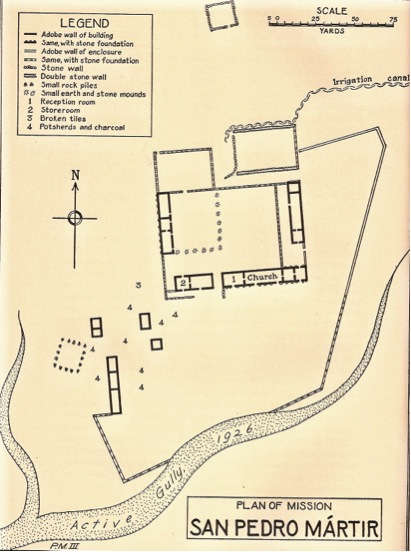

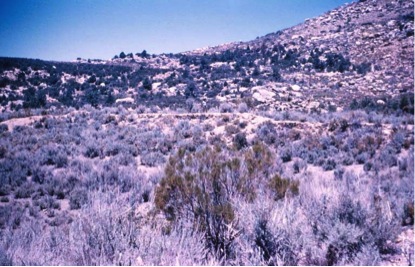

The mission was in a region where the Kiliwa Indians only visited seasonally. A large workforce was not easy to assemble without a permanent local population. The complex at Ajantequedo was large and mapped out by Peveril Meigs during his field work on the Dominican missions in 1926. It resembled a fort with defensive walls for protection. Water for mission crops came from springs on opposite sides of the valley and above the stream. Canals were built from the two springs and both ran for a half mile to the fields and to the mission. In 1926, Meigs found the mission floors were partly tiled with red 9” x 9” bricks and pieces of red roof tiles were abundant. Meigs stated that San Pedro Mártir was a “highly developed, picturesque, and unique mission”. The elevation at the second site is 5,060 feet above sea level making it the highest Spanish California mission.

In 1794 Sergeant José Manuel Ruiz wrote of the building of two bulwarks (fortifications) with cannon embrasures (openings). Ensign Alférez Bernal had been sent from San Vicente to San Pedro Mártir in May, 1796 to investigate an incident. Bernal found that some soldiers were wounded and some Indians killed in a skirmish. Arrillaga wrote in August of 1796 there was trouble with Indians “escaping.” While at San Vicente, Arrillaga learned that the neophytes of San Pedro Mártir had deserted and demanded a new padre be assigned to them.

By 1800, the population had only grown to 92. The primary crop was corn, but raising cattle was the most productive endeavor for this mission thanks to the extensive pasturelands nearby. In 1801, a new church made of adobe 17’x 69’ and a long reception room 39’ x 19’ was constructed. Also, two rooms each 19’ x 22’, a storage room 19’ x 33’ were built. Sometime after 1801, the mission went into a decline. The lack of surviving records makes the reason why open to speculation.

In 1808, Padre Ramón López wrote a report on the status of all the peninsula missions. In it he states, “The two missions in the hills, Santa Catalina and San Pedro (Mártir), cannot give what they don’t have. The minister at Santa Catalina formerly was able to send something, but now he struggles just to make ends meet. San Pedro is good for little more and likely will always be that way.” From this report, we learn that the mission existed at least until 1808. The mountain mission, from which the entire range is named after, operated for probably less than thirty years. The remaining neophytes were transferred down to Mission Santo Domingo and nothing more is known of its end or the exact year it closed. One research paper states that an especially cold winter closed the mission in 1811. Padre Mansilla of Santo Tomás has an entry in the San Pedro Mártir mission book of records in 1846, which is most curious and has caused some rumors about ‘Dominican gold’ since there are old mines and mill stones (‘arrastras’) in the area.

Dominicans who served or visited San Pedro Mártir in the following years include:

1794: Caietano Pallás, Juan Pablo Grijálva, José Loriente.

1795: Rafaél Caballero.

1797: Juan Rivas, José Loriente.

1797-1798: Mariano Apolinario.

1798: José Caulas, Miguel Lopez, José Loriente.

1803: Eudaldo Surroca.

1806: Juan Rivas, Ramón de Santos, José Portela.

1846: Tomas Mansilla. (40 years after the previous entry)

San Pedro Mártir is one of only two California missions not accessible by automobile. A two or three day backpack hike or mule ride is required to reach the site. The usual approach is east from Rancho Santa Cruz via San Isidoro, or south from La Tasajera via La Grulla.

The following articles from these authors give addition details on this most remote of the California missions:

John Robertson, 1966: http://dezertmagazine.com/mine/1966DM08/index.html (article begins on page 39)

John Foster, 1991: http://www.pcas.org/vol33n3/333fostr.pdf

Max Kurillo, 1996: http://www.pcas.org/Vol33N3/333Krilo.pdf

David Kier is co-author of ‘The Old Missions of Baja & Alta California, 1697-1834’. The book is available for purchase HERE or at the DBTC offices (call 800-727-2252).

One thought on “The Spanish Missions on the California Peninsula: #24, San Pedro Mártir de Verona (1794-1811)”