A Photographic Journey Through Baja California’s Pacific Coast Region

Book review by Graham Mackintosh

Book review by Graham Mackintosh

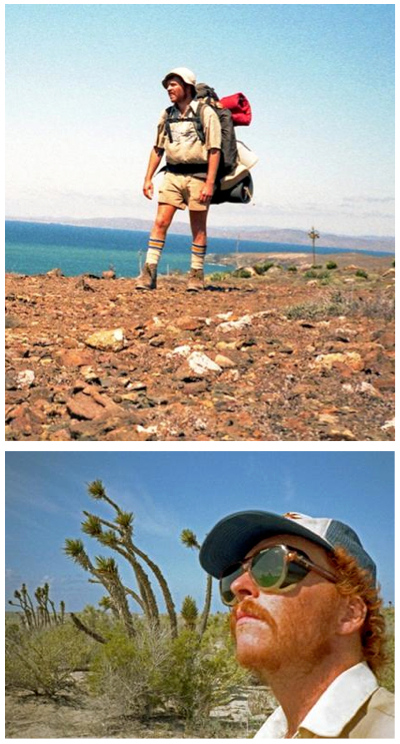

Hiking the Northern Pacific coast of Baja in 1983 I was struck by its wondrous light and astounding beauty. Carrying little film for my point and shoot 35mm camera, I had to consign countless scenes to memory. Sometimes I only had black and white print film. I rarely took more than a few photographs a day, mostly “selfies” and close ups.

When I was asked to write the Foreword for Daniel Cartamil’s new book: Baja’s Wild Side, I was happy to do so, because of the way he captured the beauty and the mood that I scarce recall.

As I said in the Foreword:

“Daniel’s book with its superb photography brought it alive once more and helped me understand why I was so drawn to the peninsula and its people and compelled against all good sense to walk its dramatic coastline. Indeed, Daniel’s keen perspective enabled me to see more than when struggling alone, eyes stinging with sweat and sunscreen, focused a few steps ahead for rattlesnakes and piercing spines. This timely and important book, while celebrating an astounding wilderness, looks back to a relatively benign and sustainable human impact, and forward to new more existential threats.”

There are currently 43 of the images from the book in an exhibit ringing the entire top floor of the San Diego Natural History Museum – an exhibit likely to be there till the end of the year, and well worth seeing. The author couldn’t be happier with the quality of the blow ups.

I recently had the pleasure of meeting with Dan Cartamil and getting to know something of his work and interests. Dan is more than a superb photographer. As I began in my Foreword:

“Dan Cartamil knows sharks, the people who catch them, and the state of the shark fisheries in Baja California. He holds a PhD from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, La Jolla, California, and has authored or coauthored over 20 scientific journal articles on the subject. His research projects have led him to spend considerable time on the Baja peninsula and have been instrumental in shaping recent shark conservation measures by the Mexican government.”

“Dan Cartamil knows sharks, the people who catch them, and the state of the shark fisheries in Baja California. He holds a PhD from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, La Jolla, California, and has authored or coauthored over 20 scientific journal articles on the subject. His research projects have led him to spend considerable time on the Baja peninsula and have been instrumental in shaping recent shark conservation measures by the Mexican government.”

Daniel is from New York City, and grew up in Manhattan. Mountain biking and Afro-Cuban percussion music are in his blood. He just returned from studying with master drummers in Cuba. He has been a musician since a little kid… percussion mostly, but also guitar, and other instruments.

Marine biology studies took him from New York to Florida, which he hated, and on to Alaska as a fisheries observer. He lived on boats out of Anchorage and Kodiak.

Wanting to get a higher degree and be in Southern California, in 2004 he entered PhD program at Scripps to study thresher sharks. His work involved tagging sharks in Southern California with electronic tags, aiming to regulate the shark fisheries better.

But he noticed that many tagged sharks crossed the Mexican border… so he initially had to give up at that point. But to answer the question if thresher shark fishing was sustainable, he needed to understand what was happening in Mexico. There were very strict regulations on fishing in Southern California, but there was concern that in Mexico they were being “harvested like crazy and the population could be decimated and we would have no idea.”

So the team went south to see what sharks and rays were being caught by the Mexicans.

They gained permission to enter Mexico and work with CICESCE and various university departments. It was a big binational project.

They were generally welcomed with open arms and generosity in the remote fish camps. They camped on the beach and obtained data on fish identifications, sex, size, etc. as the fish were brought in… and even took teeth and tissue samples. Dan authored and co-authored several studies with Mexican researchers.

They were generally welcomed with open arms and generosity in the remote fish camps. They camped on the beach and obtained data on fish identifications, sex, size, etc. as the fish were brought in… and even took teeth and tissue samples. Dan authored and co-authored several studies with Mexican researchers.

Learning how dangerous it was, everyone involved developed huge sympathy for the fishermen working 30-40 miles offshore with no GPS, or radio contact. These fishermen would often stay two nights out there and sleep on a pile of dead sharks. Occasionally, they never came back.

They discovered the Laguna Manuela carcass field with thousands of dumped mummified remains of sharks and rays, and noted 95% of the sharks and rays caught were immature, which was a big problem. Most of these fish were being harvested before they had a chance to breed.

It was observed that there were a surprising number of great white sharks caught, mostly in the 4-5 ft. range. They postulated that Vizcaíno Bay area is a critical nursery for white sharks because of its shallow continental shelf. Indeed, the bay was critical for many species of sharks, with its great mass of rays and prey species.

Using their data, the study led to the publication in 2009 of new rules for shark and ray fisheries. These rules stipulated that longliners could use no more than 350 hooks, that boats could employ no more than one net at a time, and they couldn’t be left overnight, and banned the consuming of great whites outright.

There was a definite reaction to these new rules… cool in the north, where the researchers were know, and openly—even dangerously—hostile in the south. It was a classic case of biologists and fishermen in conflict. The fishermen want sustainable fisheries, but their practices and modes of fishing are not compatible with that goal.

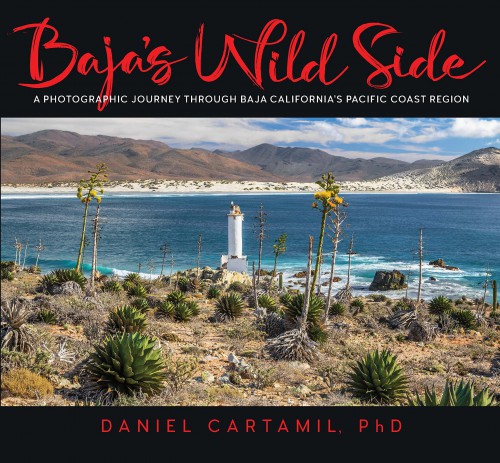

While this was going on, Daniel received a grant to promote a conservation photography project in Baja, to publish a book which became Baja’s Wild Side. With the grant he was able to buy new photographic equipment and finally do justice to the stunning scenes and vistas he could see most every day he spent below the border. It was funded by a private family foundation that believed in conservation via photography, that the public were more impacted by a single good picture rather than reams of research data.

While this was going on, Daniel received a grant to promote a conservation photography project in Baja, to publish a book which became Baja’s Wild Side. With the grant he was able to buy new photographic equipment and finally do justice to the stunning scenes and vistas he could see most every day he spent below the border. It was funded by a private family foundation that believed in conservation via photography, that the public were more impacted by a single good picture rather than reams of research data.

That grant led to two years conducting photography after his research. He got to know spots through his work. He looked at maps – and it was great to then explore, sometimes alone, where he was able to camp out till the light and conditions were perfect.

People say, how can you stand to be there in that bleak desert, but in reality so much of Baja is a place of incredible variety, and beautiful beyond belief.

His first trips coincided with the resurgence of cartel activity along the border, around 2006-2010. Most research was done at that time. So he drove down mentally planning his escape route if a vehicle with tinted windows pulled in behind.

In reality nothing happened, but when he saw fast boats leaving Laguna Manuela, and the fishermen never looking at or interacting with these mysterious boatmen, everyone was minding their own business, and Dan came to understand and liked it that way.

The scariest thing was the military coming along with machine guns, and they were mostly kids doing their service. That was disconcerting when you’re alone, feeling exposed. But Dan never met anyone that was not warm and inviting and friendly.

In Cataviña, like most tourists, he had his first exposure to cave paintings. He hired a local kid to take him to other sites, and there he saw so much art and paintings, and had the first inkling of the extent of native art.

Sure, there were dangerous incidents and times that he nearly died. He recalls the time, on a curvy road, when the wheel came off at 60 mph, and he skidded to a halt on the axle… or the time dropping to Punta Canoas, when his brakes failed, but fortunately a straight level stretch saved him in that descent.

His Chevy Silverado took a Baja beating over a decade. The hazards came and went, but they were more through travel in the backcountry rather than through meetings with drug runners.

His Chevy Silverado took a Baja beating over a decade. The hazards came and went, but they were more through travel in the backcountry rather than through meetings with drug runners.

Well we’re glad that Dan survived. And glad of his photography… to capture a moment when what remains of Baja’s Wild Side might be protected to inspire and uplift the human spirit… or equally may be lost forever.

Baja’s Wild Side is on sale through Discover Baja.

Upcoming events and presentations featured on Daniel Cartamil’s website: www.bajaswildside.com