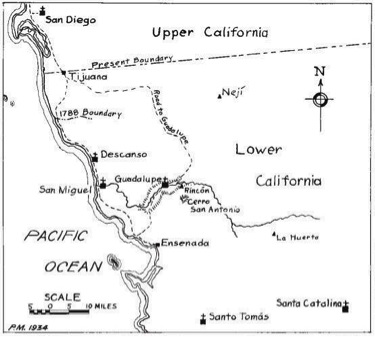

Ojá Coñúrr (Painted Rock) was the native Indian name for the location of the final mission in both Baja and Alta California. Mexico had won its independence from Spain in 1821. Dominican Padre Felix Caballero named this new mission in honor Mexico’s patron saint, Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe. The founding date has been given as June 25, 1834. The mission is sometimes called Guadalupe del Norte to differentiate it from the Jesuit founded Mission Guadalupe (1720-1795), in southern Baja California.

Padre Caballero arrived in northern Baja California in late 1814. The records show he performed a burial service at Mission San Vicente on December 15 of that year. In May, 1815, Caballero was assigned to Mission San Miguel to replace Padre Tomás Ahumada, who had been the resident missionary there since 1809. Caballero was one of just five missionaries in northern Baja California that year. In 1819, two more Dominicans arrived in Baja California and Felix Caballero was placed in charge of Mission Santa Catalina from 1819 to 1822. 1822 was a year of major events for the people of Baja California. They learned that Spain had lost Mexico after 11 years of war and they were to pledge their allegiance to the new Mexican Empire. Also in 1822, Chilean ships and soldiers, led by English Admiral Thomas Cochrane, attacked San José del Cabo, Todos Santos, and Loreto, in an attempted invasion.

Mexico’s new emperor, Agustín de Iturbide, was soon banished by General Santa Anna, and the young country became a republic. The California missions would continue to operate without any government assistance, as they had been for several years during the war. The few remaining mission padres had to survive on what they could raise or from the trading of goods with foreigners. Padre Caballero was able to succeed at Mission El Descanso, which he re-founded in 1830. Some potentially rich farmlands were just southeast in a valley called San Marcos. Caballero was anxious to develop the valley. Chief Jatiñil from Nejí, who helped Caballero build the new church at El Descanso, also helped him construct another new mission in this valley. Guadalupe, like the new church at El Descanso, was the personal project of Caballero. The Spanish mission program was over and while Mexico ordered the missions to be secularized in 1833, the law was rescinded for the California missions in 1835. They could continue operate and serve the Indians until the mission was abandoned or the current priest died.

According to the research done by Rev. Albert Nieser, O.P., Caballero built the mission for newly arriving mainland settlers, and not the Indians. Chief Jatiñil provided help for Caballero every year with harvesting crops as well as constructing Caballero’s mission buildings. Jatiñil also helped Caballero in fighting other Indian tribes that attacked Mission Santa Catalina. Jatiñil’s father had told him the land would belong to the gente de razon or‘people of reason’ (whites and mixed bloods), and the chief had accepted this reality.

The Guadalupe mission church had two altars and a choir. The mission compound had shops and a residence for the priest. Caballero made Guadalupe the administrative center of the northern peninsula missions. The mission sat on a small mesa overlooking the valley from near the center-west side. Two miles of irrigation canals were constructed down both sides of the valley. One six acre plot, just north of the mission, was where vegetables and fruit were raised. Cattle seemed to be the chief commodity with nearly 4,915 head reported in 1840, the largest of any Dominican mission. A letter to Caballero on May 29 of that year from Don Juan de Jesús Ozio however claims the count was only 1,915.

In 1836, some 400 Yuma Indians attacked Guadalupe but the garrison of soldiers stationed there were able to save the mission. More attacks came until the final one by Caballero’s own supporter, Chief Jatiñil. He revolted against Caballero because the priest continued to force baptism of his tribe and make them live at the mission. An attack in October 1839 was reported to have sacked the mission, but an eye-witness to the attack gave the date as February 1840, recorded by Manuel Clemente Rojo. Jatiñil’s goal was to kill Padre Caballero, but the padre was able to persuade María Gracia, an Indian woman to hide him in the mission’s choir. Caballero escaped death and left northern Baja California for Mission San Ignacio in the southern half of the peninsula. There he began to acquire property and attempted to have his Guadalupe mission cattle delivered to him.

On the morning of August 3, 1840, at Mission San Ignacio, Caballero said mass and drank his daily cup of chocolate. Sharp stomach pains hit him, as if he were poisoned. Felix Caballero died a few hours later. The extensive property that Caballero had would cause government officials in Baja California to frown upon the Dominicans who remained. The missions were in decline, most of the Indians were gone and the mission churches often continued to serve the newly arriving mainlanders. Dominicans were replaced by parish priests. The last California mission to close was Santo Tomás, in 1849. The last Dominicans left Baja California, from La Paz, in 1855.

By 1929 the adobe walls of Mission Guadalupe were already destroyed by treasure hunters but some of the wall’s stone foundation was present and measuring 60 yards on one angle and 30 yards on the other. Pieces of red floor tiles were inside the angle. It was reported that broad steps led down the slope from the mission to two cement water tanks fed by a spring.

In recent years, the mission site has been developed as a historical park and includes a museum. It is located in Francisco Zarco (the government name for the town of Guadalupe), about 1 mile from Highway 3. Take the paved side road going into town from the gas station. In about a mile, turn left at the cross street (where the road ahead becomes divided). The mission and museum are overlooking the river valley.

The missions of Baja California are both historically colorful and intriguing as to their existence. That such great effort was made in such extreme conditions illustrates the enthusiasm and commitment the missionaries had for their work in peninsular California. The native Indians who survived mixed with the mainlanders and foreigners who came to the peninsula. The tribes in the north were better able to survive the changes and live today in villages on the Colorado River delta, and near the missions of Santa Catalina and Guadalupe.

Thank you for your interest in the old missions of Baja California and please see additional mission photos and information on our Facebook page: facebook.com/oldmissions and my web site: vivabaja.com/bajamissons

The Guadalupe mission walls were just back of the cactus on top of the embankment. Photo by Peveril Meigs in 1929.

David Kier is co-author of ‘The Old Missions of Baja & Alta California, 1697-1834’. The book is available for purchase HERE or at the DBTC offices (call 800-727-2252).

One thought on “The Spanish Missions on the California Peninsula: #27, Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe (1834-1840)”